Who's a Good Grim Reaper? Falling in Love with Death, Dogs, and the Day

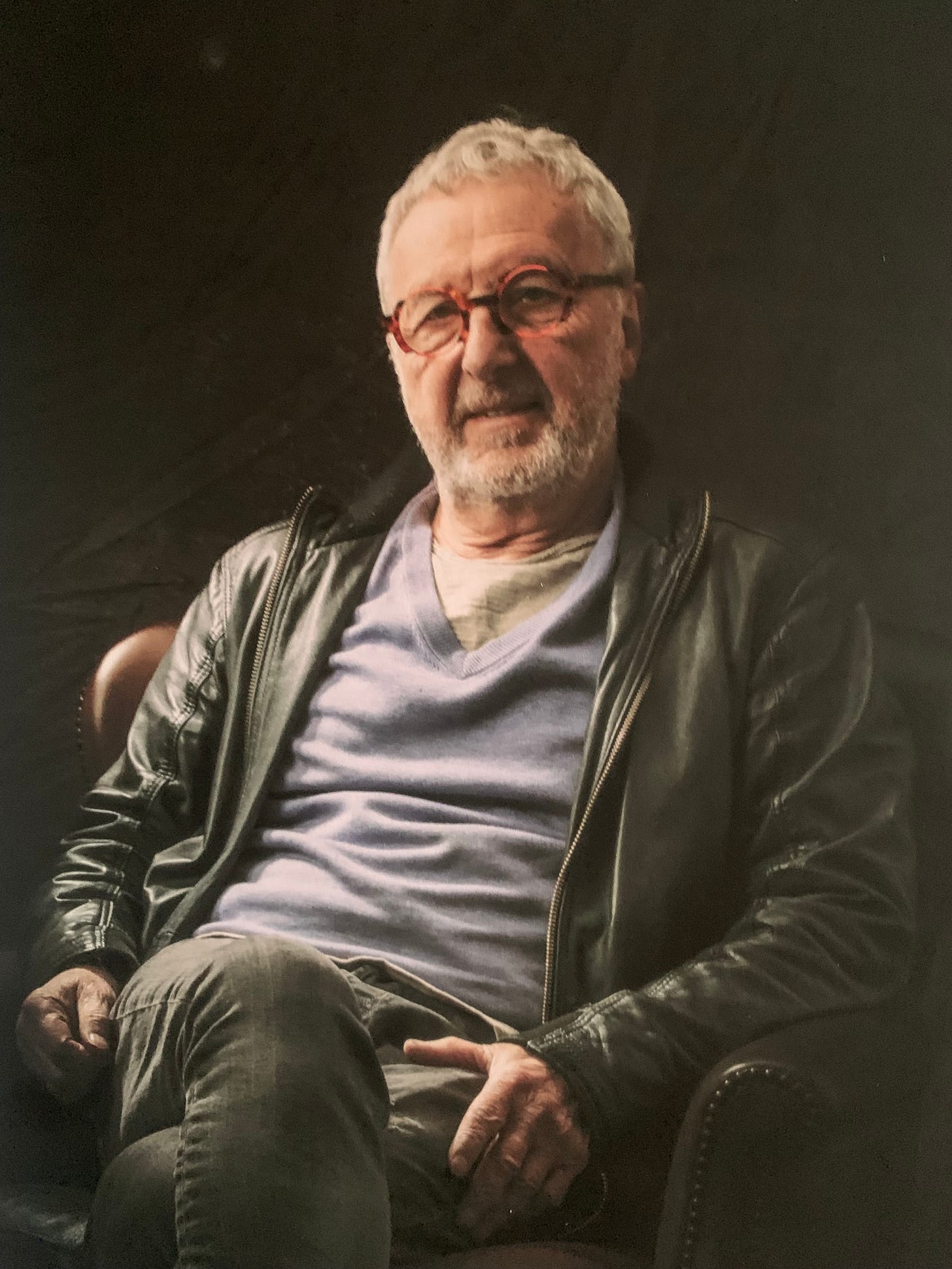

An interview with Robert Garland

Robert Garland is the Roy D. and Margaret B. Wooster Professor Emeritus of the Classics at Colgate University. He is the author of many books, including The Greek Way of Death, Wandering Greeks, Athens Burning, and most recently What to Expect When You’re Dead (Princeton). He has also recorded six courses for the Great Courses, most recently God Against the Gods. He lives in Brooklyn and has a son and a daughter.

I first fell in love with death, or rather with the dead, when I was about 8-years old…

How did you first become interested in this subject, ancient history and death?

I first fell in love with death, or rather with the dead, when I was about 8-years old, staring down at EA 32751, aka Ginger, in his glass case in the British Museum, and somehow realising that this was the fate of all of us. He’s a naturally mummified mummy, which is to say he’s all dried up but otherwise looking very much as he might have looked the day before he died 3,600 years ago. Then I found that I liked cemeteries to ruminate in, but only if they’re overgrown and dank, like Highgate Cemetery, not if they’re carefully tended. Being in the presence of death is very enlivening, I find.

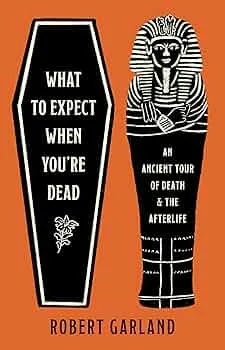

Tell us about What to Expect When You are Dead: An Ancient Tour of Death and the Afterlife.

It’s a very personal exploration. I address the reader in the second person because the book tries to establish a bond between all the different cultures I talk about and the reader. I think going back and looking at how humans have dealt with death and thought about death for millennia is actually quite helpful, because in the end we’re all in the same boat, and if one thing is certain it’s that we don’t know any more about what happens after death than our Neanderthal ancestors, who, incidentally, cared for their dead just as we do. So I look at Mesopotamians, Hebrews, Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, Zoroastrians, Etruscans, Early Christians and Muslims to find a common denominator as well as significant, eye-catching differences.

If you could adopt one ancient belief or practice related to death from any of the civilizations mentioned (Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Hindu, etc.), which would you choose and why? How do you think it would resonate with modern perspectives on mortality?

From antiquity onwards, humans have had difficulty at times establishing when death has occurred. Even today, or perhaps especially today it isn’t simply something that happens instantaneously. There’s clinical death and there’s brain death. And, of course, in the Victorian Age, people were terrified at the thought they might be buried prematurely. Some people claim to have come back from being dead after having had a near death experience or NDE. In Plato’s Republic Er the Pamphylian claims he’s seen what awaits us in the world to come. But sticking with what practice would I choose, I’m very much in favour of the Zoroastrian sagdid ceremony, whereby you bring in a dog to sniff whether the deceased is actually deceased. I love dogs and I think they have deep insight, and I’m sure they’re more acute in detection than more modern methods of determining whether death is death, so to speak.

Do you have a favorite quote that you use?

There’s nothing better than the Latin poet Horace’s line,

Carpe diem.

Odes 1.11.

pluck or seize the day, because after all that’s what life is all about, and it’s what death teaches us.

Another one is from Protagoras, On the Gods.

Concerning the gods, I know neither whether they exist or don’t exist. There are many obstacles to knowing. The brevity of human life and the complexity of the subject.

The same is true about what we (don’) know about death.

I think the realization of death is not only uplifting and, as I said, enlivening, but it also helps us move beyond what divides us.

What advice would you give someone who wanted to learn more about what you do?

I’d probably say, start by reading the last book of Homer’s Iliad. It’s where old king Priam comes to beg for the body of his son Hector, whom Achilles has killed. Achilles was full of rage toward Hector for killing his best friend, but that rage evaporates when Priam secretly steals into his tent, risking his life for his son’s body. These two deadly enemies suddenly see in each other fellow human beings—Priam, Homer tells us, takes the man-slaying hands of Achilles and appeals to him, and in that moment, they transcend difference and enmity as compassion prevails. I think the realization of death is not only uplifting and, as I said, enlivening, but it also helps us move beyond what divides us.

The book I’m writing now is called Everything You’ve Always Wanted to Know About Love and Sex in the Ancient World But Weren’t Around to Ask. Sex and love naturally follow death!

Suppose you were able to give a talk or workshop at the original location of Plato’s Academy, in Athens.

I think it’s a great idea. I’m excited by the fact that Plato’s Academy will be reborn. The philosophical schools were closed down by the Christians because philosophy asks questions and doesn’t accept dogmatic answers. I’m a great fan of the Platonic dialogues that are “aporetic” – the ones that ask questions without supplying answers. That to me is the source of wisdom, acknowledging like Socrates one’s pitiful ignorance about the things that really matter, yet ceaselessly searching for answers.

What question would you like to leave us to think about?

What are you going to do tomorrow fully aware that it might just be your last day on planet Earth? How will you behave towards the people you casually encounter? How will you seize the day?

Great interview. Never forget the wonder of it all or miss the moment. After all, the death rate is holding steady at 100%.