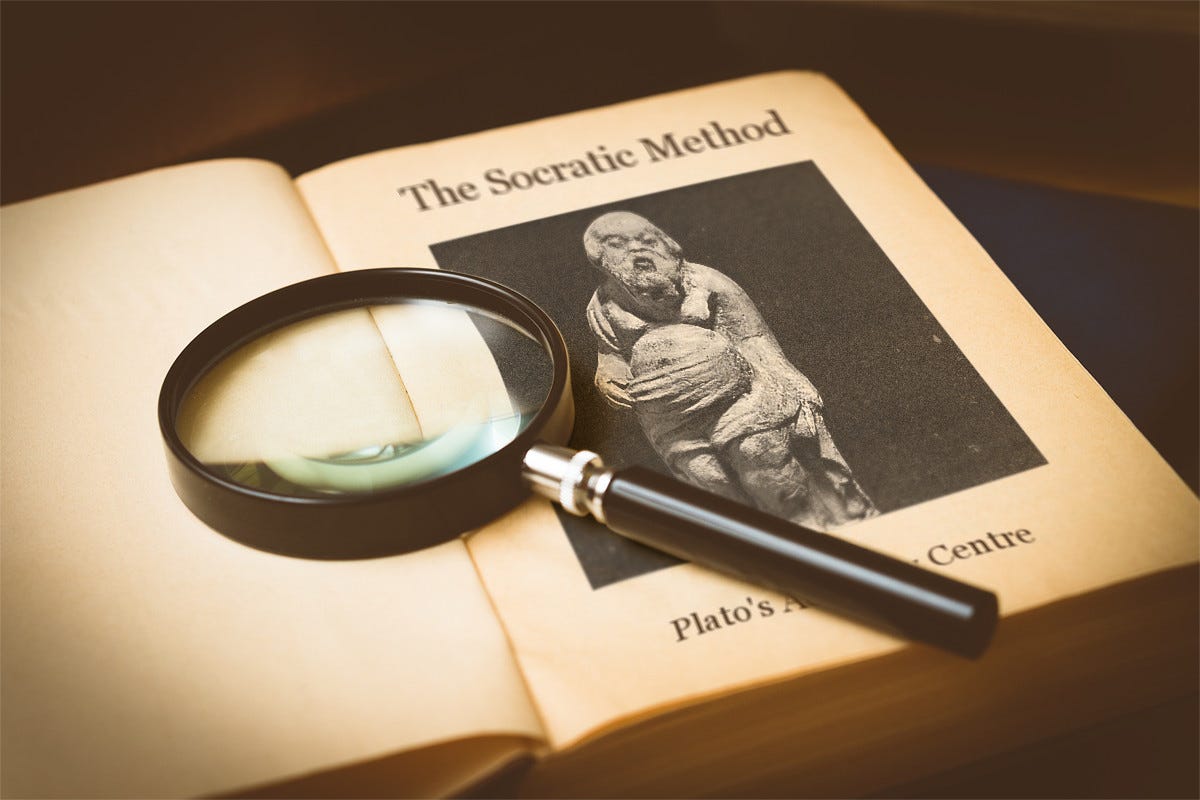

This episode is part of the Plato’s Academy Centre course on the Socratic Method. In this lesson, we will be learning who Socrates was, and why he became famous. We’ll also begin looking at the origins of the Socratic Method, and the role it played in his philosophy.

There is no greater evil one can suffer than to hate reasonable discourse. – Socrates in Plato's Phaedo, 89d

There is an optional Facebook Live video of this lesson. NB: You do not need a Facebook account to watch the video but if you want to log in and follow our page, we'd appreciate that.

Asked whether any man was wiser than Socrates, Apollo replied through his priestess, the Pythia, declaring: Of all living men, Socrates is the most wise.

Socrates of Athens

Let's begin with a brief introduction to Socrates, the quintessential Athenian philosopher. Socrates left behind no writings. We know of him primarily through the Dialogues of Plato, his most celebrated student, which portray Socrates discussing philosophy with various acquaintances. Plato's earlier dialogues are believed to be more faithful depictions of his teacher, whereas in those he wrote later he often put his own doctrines into the mouth of Socrates.

Plato is not our only source, however. We also have many Socratic dialogues by Xenophon, a good friend of Socrates who became a famous military general. We even have a satirical depiction of Socrates in the comedies of Aristophanes, particularly The Clouds. There are also many references to him in other ancient sources, although often of uncertain reliability. For example, in Diogenes Laertius' Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, Socrates is described as "the first who discoursed on the conduct of life, and the first philosopher who was tried and put to death."

Socrates and the Delphic Oracle

The key details of his life are as follows. Socrates was born in the early 5th century BC. His father was a stonemason or sculptor, and his mother was a midwife. He distinguished himself during his military service in the Peloponnesian War, when Athens and her allies fought against Sparta and hers. Although by no means wealthy, with the support of his friends, Socrates was eventually able to leave his stonemason's workshop and dedicate the rest of his life to the study of philosophy.

At some point, probably when Socrates was approaching midlife, his childhood friend, Chaerephon, journeyed from Athens to the Temple of Apollo in nearby Delphi, to put a question to the Oracle. Asked whether any man was wiser than Socrates, Apollo replied through his priestess, the Pythia, declaring: Of all living men, Socrates is the most wise. Socrates claimed that he was shocked by this. He set about questioning everyone he met, from all walks of life, in order to put the god's assertion to the test and establish the true nature of wisdom.

The Socratic Method

Greek philosophers who came before him, such as Pythagoras and Anaxagoras, had speculated on the nature of the cosmos and laid down moral dogmas for their students. Socrates, however, became famous for his trademark "question and answer" method. It was designed to cure himself and others of a sort of intellectual conceit: the belief that one knows something that one does not know, such as what is good, or what is virtuous.

It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so. — Mark Twain?

Although that quote is widely attributed to Mark Twain, there’s no evidence, ironically, that he ever said it — perhaps it just ain’t so. Nevertheless, the point it makes is similar to Socrates’ point about the dangers of intellectual conceit.

Casting himself more in the role of great student than great teacher, Socrates began by denying that he actually knew much of importance. This, however, was widely viewed as a stratagem, known as "Socratic irony".

I myself know nothing, except just a little, enough to extract an argument from another man who is wise and to receive it fairly. – Socrates in Plato's Theaetetus, 161b

Socrates' question and answer method was therapeutic. Indeed, Plato actually describes it as a philosophical “therapy of the psyche”, or as we say a psychotherapy. It focused on the values and beliefs held by the individuals with whom he was speaking, in a way that affected them quite deeply at a personal level.

Anyone who is close to Socrates and enters into conversation with him is liable to be drawn into an argument, and whatever subject he may start, he will be continually carried round and round by him, until at last he finds that he has to give an account both of his present and past life, and when he is once entangled, Socrates will not let him go until he has completely and thoroughly shifted him. – Plato's Laches, 187e

Along the way, Socrates exposed the intellectual pretences of many influential figures in Athenian society. We might say he rocked the boat by asking too many questions, and paid the price for this when his enemies charged him with impiety and corrupting the youth.

The Death of Socrates

Socrates' trial in 399 BC was a defining moment in the history of Western philosophy. The jury, of 500 Athenian men, found him guilty and sentenced him to death by forced suicide – he was made to drink hemlock. His execution sent shockwaves through the ancient world, turning him into something resembling a philosophical martyr. Plato was inspired to found The Academy, the first scholarly institution in Western history. It was located outside the city walls, in one of the gymnasia or recreational grounds frequented by Socrates.

The ability to reason well, like Socrates, by patiently asking the right questions and tolerating disagreement, is arguably becoming a lost art today, particularly on social media. However, in the rest of this course, we're going to learn how to use the Socratic Method. We'll also explore how the Socratic Method influenced questioning techniques used today, such as those central to modern cognitive psychotherapy, and how other critical thinking skills can help us to engage in constructive dialogue about important issues.

What do you think we can learn from Socrates? Let us know in our Facebook Community. Or tag @PlatoAcademyCen on Twitter and use #Socrates to continue the conversion there.

Regards,

Donald Robertson

President of The Plato's Academy Centre

Share this post