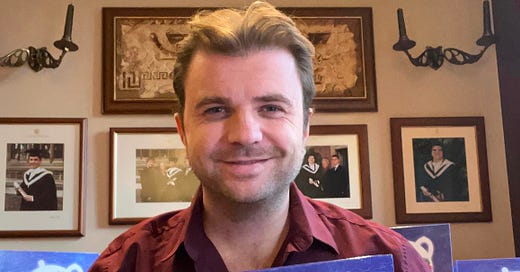

Sasha Zouev is a PhD philosophy researcher at the University of Leeds as well as a children's book author. His new book, Tim and the Giant Teapot, is one of the first children's picture books to deal with topics concerning critical thinking, humanism, and atheism. It can be read as an introductory text to epistemology for very young children.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Plato's Academy Centre Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.