Below is an excerpt from Susan Stewart’s The Ruins Lesson: Meaning and Material in Western Culture. This comes courtesy of University of Chicago Press.

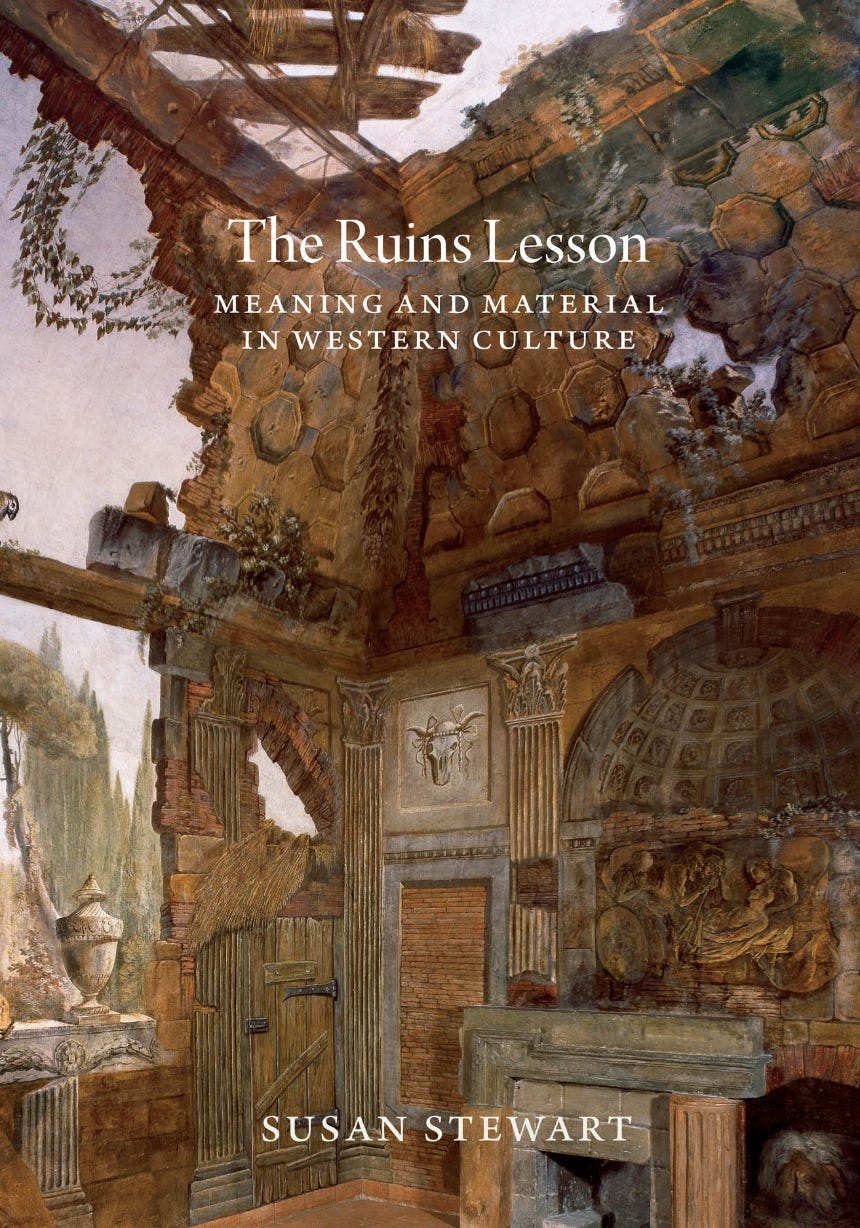

How have ruins become so valued in Western culture and so central to our art and literature? Covering a vast chronological and geographical range, from ancient Egyptian inscriptions to twentieth-century memorials, Susan Stewart seeks to answer this question as she traces the appeal of ruins and ruins images, and the lessons that writers and artists have drawn from their haunting forms.

Stewart takes us on a sweeping journey through founding legends of broken covenants and original sin, the Christian appropriation of the classical past, and images of decay in early modern allegory. Stewart looks in depth at the works of Goethe, Piranesi, Blake, and Wordsworth, each of whom found in ruins a means of reinventing his art. Lively and engaging, The Ruins Lesson ultimately asks what can resist ruination—and finds in the self-transforming, ever-fleeting practices of language and thought a clue to what might truly endure.

The Ruins Lesson

Such positive attitudes toward the signs and effects of wear and age have had a powerful and long-lasting influence on the field of architectural conservation. In the 1860s and 1870s, proponents of “scientific” restoration, who followed Viollet-le-Duc’s mandate that restoration required a building be “reinstated” to a condition of completeness which may never have existed at any time, argued against those who followed John Ruskin and William Morris and claimed ancient buildings should be conserved and protected in their existing state. Ruskin, condemning Romantic attitudes toward ruins, wrote in 1849, “Look the necessity full in the face, and understand it on its own terms. It is a necessity for destruction. Accept it as such, pull the building down, throw its stones into neglected corners, make ballast of them, or mortar, if you will; but do it honestly and do not set up a Lie in their place. ”In the twentieth century and into the present, restorers have turned against both simulacral practices of tearing down and ripping out parts of structures with the aim of unifying an appearance of period style and the conservation of buildings as examples of national and collective aspirations. Instead, they have aimed to preserve a record of the ongoing continuity of buildings and sites.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Plato's Academy Centre Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.