History often appears clear and well-defined in retrospect, but this clarity can be deceiving. It overlooks the nuances and ambiguities that existed at the time. In Seneca's case, this has led to a negative perception of his association with Nero, overshadowing his accomplishments and casting doubt on his character. It's tempting to judge Seneca harshly for his involvement with Nero, but doing so ignores the complexities of the situation and the potential for positive change that existed at the time.

is Seneca the author of this satire?

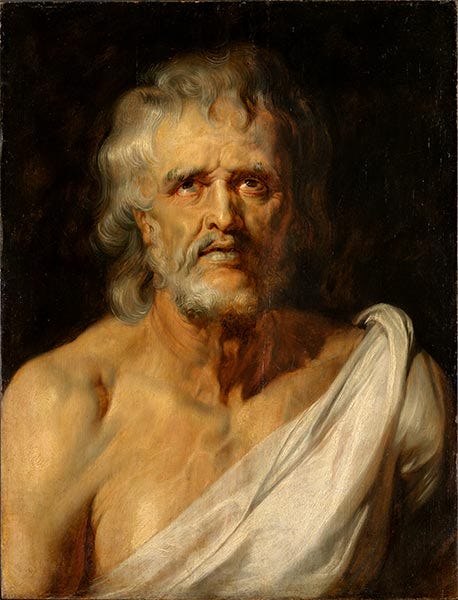

This is the necessary historical background to an interesting question of attribution (one that has always been met with a certain lingering skepticism) and which works to Seneca’s discredit, completing the prejudicial portrait created by this historical hindsight. Namely, in assigning to him the cruel satire The Apocolocyntosis, Seneca is presented from practically the first day as a hypocritical advisor to the young Nero, and a fairly disreputable philosopher. It needs to be said that this serves as a black mark, certainly against Seneca, but also against Stoicism and philosophy more broadly. But is this actually the case—is Seneca the author of this satire? Might it not be the case that the negative valuation of historical hindsight has overshot the mark in this instance? Has Seneca been judged to be thoroughly bad from how we today see the reign of Nero, and so anything distasteful can be assigned to him without further ado? Questioning the attribution of this satire, then, is something like the rescue of Seneca’s honour.

This is the argument I make in my study, where a close analysis on various topics of genre, textual, and historical themes is brought to the fore to question this attribution. Also, and most importantly, the prior work of a past generation of classicists who challenged this attribution is brought back up to the notice of the present day. In this sense, the work is not the product of individual idiosyncrasy, but a collective endeavour, and really a question of competing paradigms of interpretation. The main distinction could be drawn: is Seneca completely corrupt and the author of a brutal satire, or rather is there a shade of gray where we find this attribution can not be sustained?

To say that the work comes from Seneca means assuming a highly self-refuting way of operating, as the philosopher would then ridicule his philosophical school in the satire while promoting it in his confirmed published works.

First, in using a close analysis on the theme of philosophy as it appears in Menippean satire (the genre in which the work belongs, due to its mixture of poetry and prose) the work is seen to be an outlier in its proposed minute field, that is to say, Menippean satire authored by a philosopher. Notably, the satire does not praise philosophy, and even more interestingly, it condemns philosophy. To say that the work comes from Seneca means assuming a highly self-refuting way of operating, as the philosopher would then ridicule his philosophical school in the satire while promoting it in his confirmed published works. The satire also ridicules the deification of Claudius, which was one of the first official acts of the new government that Seneca presided over. Does not basic political logic imply that Seneca would not so seriously undercut himself and his position by this levity?

There is also the interesting note that the satire hits out at Greeks and foreigners more broadly—but Seneca was himself a provincial Spaniard, and so how could he be expected to act like a Roman nativist? This is to say nothing of this contradiction with the cosmopolitanism of the Stoic mindset. These are just a few of the issues that are treated in the study (there are many more that cannot be treated here for reasons of space) and which can be raised to question this attribution. The final thing to note is that this ascription to Seneca is in reality a Renaissance guess based on a reading of a phrase in Cassius Dio, allied to a questionable medieval manuscript transmission (which first calls the work not the Apocolocyntosis, but the Ludus). The titles proposed for the work do not match, and these mismatches can be resolved by theorizing a reference to a lost work of Seneca’s, and a medieval misattribution.

But, as I submit in the study, the real issue is that there is an inherited negative valuation concerning the Neronian era which sees it as completely black, and this colours perceptions of its primary advisor. There is an inherited Christian blackening of the period (as Nero was the first to act against the Christians) which is difficult to combat because it is concordant with some, but not all, of the evidence. And for what is theorized as a uniquely bad reign, one then has a uniquely hypocritical advisor, and so a vicious satire can be assigned to Seneca on the basis of this negative perception.

But it needs to be asked: is the Neronian period an unmitigated tyranny from its inception, and all who associate with it are to be tarred with its later crimes—or rather, did this regime appear to its contemporaries as something that could be shaped and reformed for the greater good? Trajan, for one, is reported to have said that the initial five years of Nero’s rule, the quinquennium, were one of the best periods for imperial Rome. In these five years when Seneca was in power, he actually made Nero’s rule appear favourable to the society of the time.

Clearly, Seneca made the decision that the Roman Empire could be successfully guided, that it did not have to be an unprincipled despotism, and that serious political principles could be observed within an imperial framework. Judging from the later period of the Good Emperors, one has to say that Seneca made a reasonable evaluation of the potentialities within the Roman Empire. He is, then, a practical and talented Stoic, who demonstrated his political virtue in guiding the Roman Empire to some of its best years since Augustus, which foreshadowed the later period of the Good Emperors, crowned by another Stoic, Marcus Aurelius. When Seneca is seen in this light, as a positive advisor during his period of influence, it is impossible to assign him this satire, as the unattractive tendencies in the satire are diametrically opposed to his confirmed political presence during this time. With this attribution shaken, Seneca is restored to his true philosophical stature, as a talented and practical Stoic, a beneficial political advisor and influence for some of Rome’s best years under the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

The larger study on “Seneca and the Authorship of the Apocolocyntosis” can be accessed here.

-Alexander R. Hufford

BA, History, University of Virginia

MA, Classics, University of Wales, Trinity St. David

PhD student, Philosophy, Stony Brook

Alexander R. Hufford spent seven years as a young man in Athens, Greece, studying and teaching English, being inspired by the ancient world and the Modern Greeks. Since that time he has resumed an academic path, completing an MA in Classics at the University of Wales, Trinity St. David, and now is a PhD student in Philosophy at Stony Brook University.